Territorial disputes over islands are not uncommon around the world. Some of these disputes have been solved in a peaceful way: through negotiation, arbitration, or international judicial decision. Now, have you heard of countries in Northeast Asia consider sending territorial disputes to court for legal settlement, or starting a negotiation? Citizens from Korea, Japan, or China may confidently answer the question of which country has the right to occupy one of these islands definitely their own country, but rarely can they explain the logic supporting the argument. They just accept the arguments as if they are laws of nature, like “the sun rises in the east and sets in the west.” The reason for this situation is because each of these islands consist of each country’s history, which means it has more significance than just the past: it has contextual meaning for the current situation.

Viewing History: Interpretation Rather Than Fact

There are two views in the study of history: history as a fact of “what actually happened” and history as a “dialogue between the past and present.” If every historian in the world takes the former view, it would be easier to find out what happened in the past based on facts. Unfortunately, there are more historians who take the latter view, and that is the reason why we should read not just Kissinger’s Diplomacy, which is written mainly based on the author’s interpretation, but also other books, which can tell you dry facts, to find out what happened in modern history of western diplomacy. Moreover, given the environment of highly contextualized culture, one may be inclined to guess that almost all histories in Northeast Asia do not provide “facts itself.” Here are some substantial examples.

(Case1) Removal of history is an effective tool to glorify a current ruler. Suppose you are a conqueror of a kingdom in Northeast Asia. You just enter the palace in the capital city of the former kingdom. What will you do first for your brilliant future? In most cases in Northeast Asia, the conquerors of history chose to collect historical records of former age, and, depending on the content, destroy them. The exact same thing happened in Korea during the colonial era under imperial Japan. Because evidence supporting Japanese emperors’ origin from Korean peninsular could weaken legitimacy of the regime, which enshrined the worship of the emperor as an absolute authority, the Japanese government officially and unofficially gathered and threw away records of ancient history. That is one of the biggest reasons why current Korean studies on ancient Korean history are largely based on Chinese records.

(Case2) Sometimes rulers highlight a historical figure aiming an analogy with themselves. Admiral Yi Soon-shin, who had dedicated his whole life to save his country from Japanese invasion between 1592 and 1598, is one of the most prominent heroes in Korean history. One reason why Koreans love him is because of the tragic elements of his story. During the wartime, politicians, who chose to escape from the capital city rather than to fight against the enemy, just stuck to partisan discussion. And because Admiral Yi had maverick stance, political factions easily doubted his report of success in battlefield as a trial to catch king’s confidence from the aides who had followed the king’s escape. So many politicians in power accused the admiral of intriguing treason. In spite of unbelievable success without any loses, due to the hostile political environment to him, the admiral had never experienced glorious days in his lifetime, which tragically ended at the last battle. The contradiction of the admiral’s patriotic dedication and politicians’ selfishness is oddly analogous to the circumstance in 1960 right after the democratic revolution of April 19th, when there was a serious confrontation between political factions, and during which the army guarded the country from enemies from the north. Admiral Yi’s story might provide legitimacy to the President Park Chung-hee’s coup a year later not just to save the country, but also to avoid repeating the historical tragedy. It’s not a coincidence that the construction Admiral Yi’s statue at the center of Seoul took place in 1968, and the renovation of the Admiral Yi’s shrine with a signboard was written by President Park in 1967, under the president’s ruling.

(Case3) From time to time political motivation functions as a machine for rectify distorted history. In Korea, democratic movements have not always been memorized as respectful. May 18 Democratic Movement, called 5.18 (o-il-pal, in Korean language) in Korea, was a courageous protest in 1980 against another dictator, Chun Doo-hwan, who took over the government after the death of a long-time dictator, President Park. Although led by students and white collars, it was accused of a rebellion motivated by spies from North Korea during the administrations of President Chun and his military successor. The South Korean government totally prohibited any refutation of the official stance, as doing so meant that one could be punished as a sympathizer for the Communist enemy. It was not until 15 years later, when the first civil president Kim Young-sam was elected, May 18th was restored and honored as a legitimate democratic movement. That’s not the end of the aspiring story, however. There had been long and extensive hearings in the National Assembly, and the legislature made a special law to punish those who committed violent political suppression, under which two former presidents were prosecuted.

(Case4) Without background knowledge, you may immerse yourself into the age and context of a historic record. Have you ever read the Romance of the Three Kingdoms? If so, I guess you may be on the side of Liu Bei(劉備) and Zhuge Liang(諸葛亮), and support their legitimacy of reunification of the whole continent. However, once you also read the Records of the Three Kingdoms, which is part of the Twenty-Four Histories Canon, you may change your thinking: Cao Cao(曹操) was the single most powerful and plausible man who had the potential to stabilize the continent. The difference of the readers’ sympathy came from the background of the books. The Romance was written during the Ming Dynasty, which needed to encourage Han Chinese pride after a long reign under the Yuan Dynasty led by barbarians from Mongolia. So, in that context, it was natural to highlight Liu Bei, who had emphasized his legitimacy as an offspring and heir of the Han dynasty. On the contrary, the Records were written under the Jin Dynasty, during which the royal family originated from Cao’s Wei Dynasty.

How Do You “Interpret” Current Territorial Issues?

Now I hope you have some more perspective of the viewpoint from Northeast Asia. If you are a leader of a country with highly contextualized history, you would never concede to any idea or historical fact that would potentially weaken your legitimacy. Let’s take a territorial dispute for example: the Dok-do (Takeshima, in Japanese) issue. From the Korean perspective, the first time there was an official dispute over this island was around 1905, the year that the Chosun Dynasty was substantially colonized by Japanese forces. From Japan’s perspective, during the negotiations of the San Francisco Treaty in 1951 to restore its status as an independent state, Dok-do was designated as a Korean territory till the fourth draft. However after the further negotiation, the island was excluded from the list of Korean territory in the final text, which can be interpreted as American approval of restoring Japanese sovereignty over the island, as well as over the other regions. So, especially for a Japanese far right politician, Dok-do could symbolize a full restoration of national glory. I cannot imagine any leader who would be willing to gamble a nation’s symbol of either hostile history, from the Korean side, or of pride, from the Japanese side, on an arbitrary compromise.

How To Cope With Too Much Subjectivity In Interpretation?

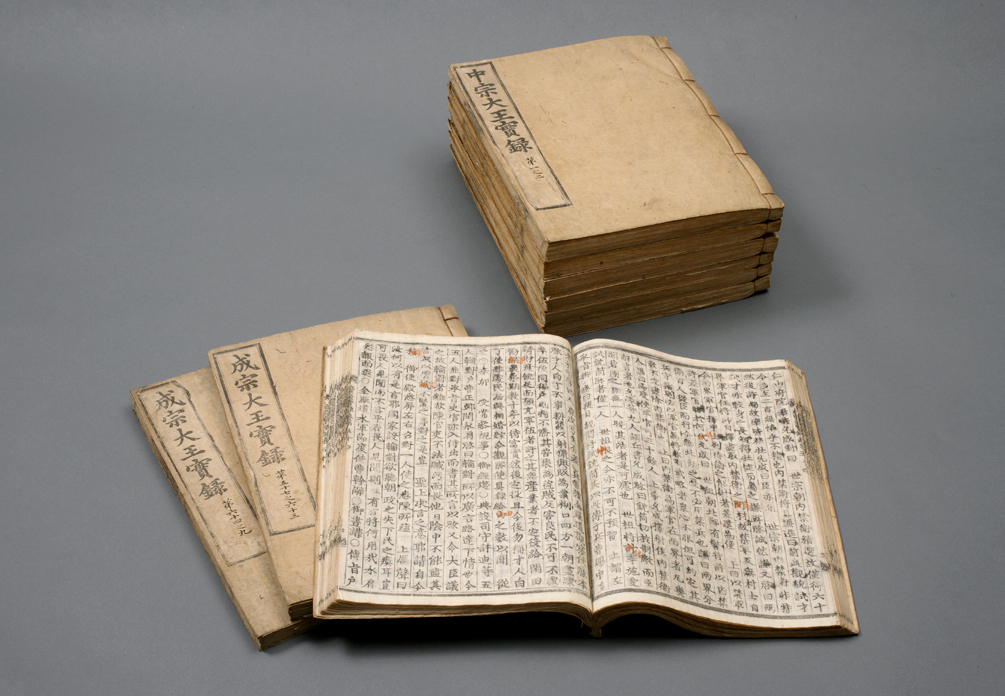

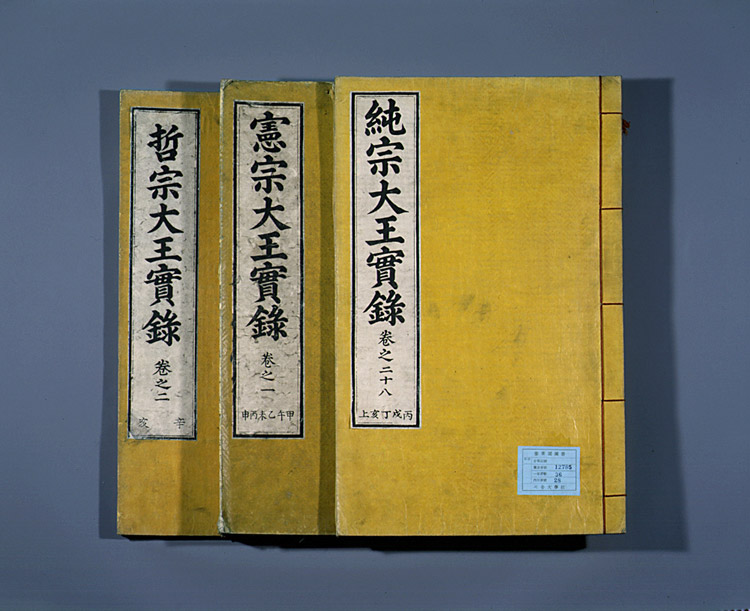

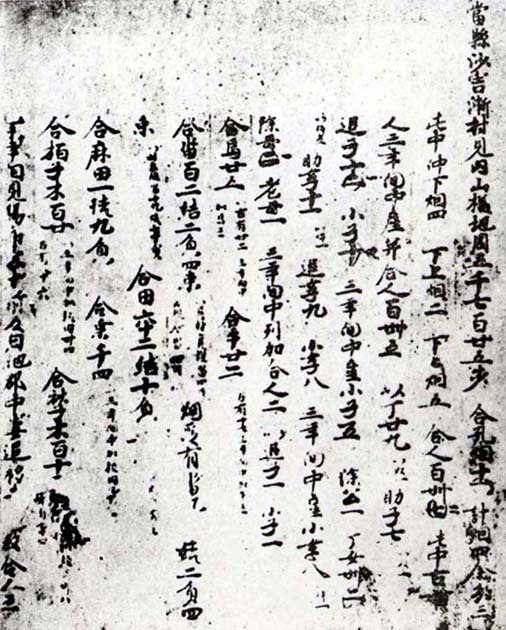

The most important thing in Northeast Asian history is to find out the firm factual truth. Because most people in the region recognize the problem of excessive subjectivity prone to the present power, there have been efforts to mitigate distortion by power and preserve facts. In China, almost every book of the Twenty-Four Histories Canon deals with history at least 100 years before the point of being written. In Chosun Dynasty, there was a position called sagwan(史官): they were officials who wrote every word from and to the king. The record was not publicized even to a king in throne, not until he dies. The idea beneath this practice is conserving facts ultil a proper time for an assessment free from the king’s absolute power. As long as the facts remain, its intrinsic value enables fair evaluation as time goes by, while interpretation can always be changed depending on political circumstances.